The United States on Wednesday declared 23 species extinct, including one of the world’s largest woodpeckers, dubbed the “Lord God Bird.”

The announcement came via the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), which proposed to remove the birds, mussels, fish, as well as a plant and fruit bat from Endangered Species Act protections because government scientists have given up on ever finding them again.

“With climate change and natural area loss pushing more and more species to the brink, now is the time to lift up proactive, collaborative, and innovative efforts to save America’s wildlife,” said interior secretary Deb Haaland in a statement.

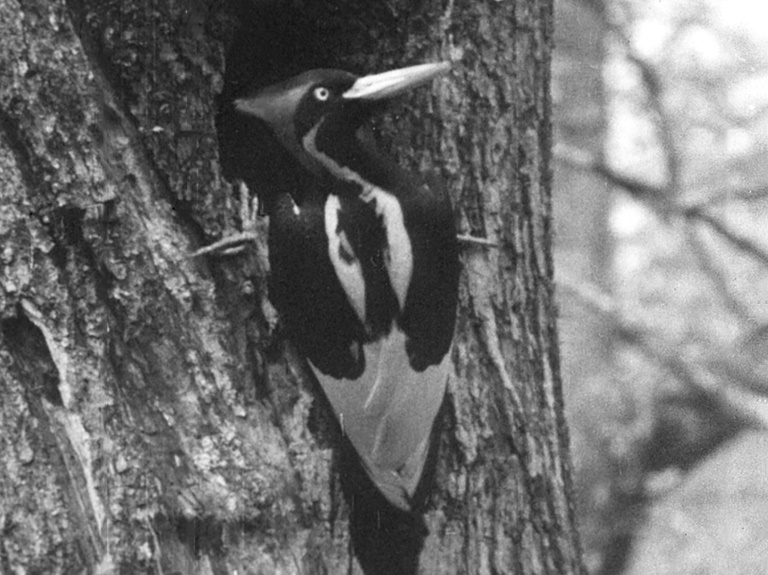

Perhaps the most iconic of the species was the Ivory-billed woodpecker, with the last indisputable evidence of its existence coming in the 1940s.

Noted for its striking black-and-white plumage, pointed crest and lemon-yellow eye, it has been something of Holy Grail for birders in recent decades, with numerous unconfirmed sightings over the years in the southeastern US.

“The fundamental thing that drove the woodpecker down to near extinction was the loss of the southeastern first growth forests, which really started taking place after the Civil War,” John Fitzpatrick, director emeritus of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, told AFP.

Fitzpatrick was part of efforts to search for the bird in Arkansas and other regions in the mid-2000s — but added that, while he agreed with the government about its decision regarding the other bird species, he believed there is still hope for the woodpecker.

“Every decade there have been reasonably credible reports coming out of the US, and in the 1980s out of Cuba, that it still existed,” he said.

The species was revered not just by Alexander Wilson and John James Audobon, considered the founding fathers of ornithology, but also by collectors who hunted them.

Its nickname, “Lord God Bird,” was said to be derived from the expression “Lord God, what a bird,” said Fitzpatrick.

Other species declared extinct include Bachman’s warbler, a songbird last documented in Cuba in 1981, and eight species of freshwater mussel, which rely on healthy streams and clean reliable water.

Eleven species from Hawai’i and Guam are included in the list, including the Kauai akialoa and nukupu’u, known for their long, curved beaks, and Kauai ‘o’o that was said to have a haunting call.

Also lost was San Marcos gambusia, a freshwater fish from Texas last spotted in 1983.

– Climate pressure –

Despite the sad news, Fitzpatrick said there was some cause for optimism.

Since it was enacted in 1973, the Endangered Species Act has prevented the extinction of 99 percent of plants and animals under its care.

These include bird species like the whooping crane, which numbered as few as 16 individuals in the 1940s but have since recovered to 500 or 600.

On the other hand, today’s endangered species also have to contend with the pressures of climate change.

Saltmarsh sparrows for example live in coastal marshes that are being rapidly disrupted by sea level rise.

Tiera Curry, a senior scientist for the Center for Biological Diversity, praised President Joe Biden’s administration for requesting a hefty $60 million increase in endangered species protections, but criticized the fact a new FWS director had yet to be appointed.

“Extinction is not inevitable. It is a political choice. Saving species isn’t rocket science. As a country we need to stand up and say we aren’t going to lose any more species to extinction,” she said.