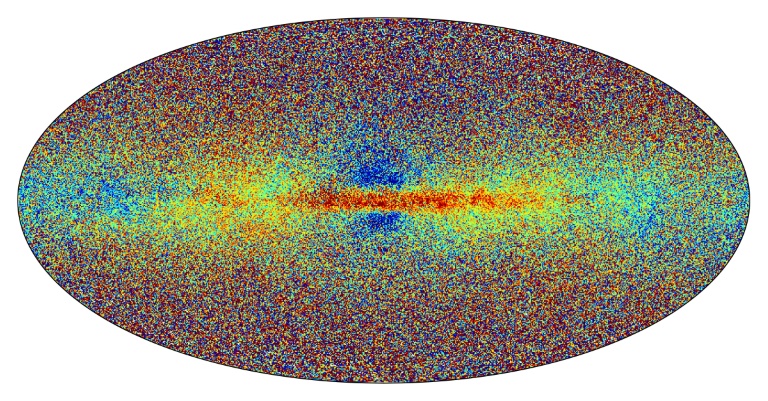

The Gaia space probe on Monday unveiled its latest discoveries in its quest to map the Milky Way in unprecedented detail, surveying nearly two million stars and revealing mysterious “starquakes” which sweep across the fiery giants like vast tsunamis.

The mission’s third data set, which was released to eagerly waiting astronomers around the world at 1000 GMT, “revolutionises our understanding of the galaxy,” the European Space Agency (ESA) said.

ESA Director-General Josef Aschbacher told a press conference that it was “a fantastic day for astronomy” because the data “will open the floodgates for new science, for new findings of our universe, of our Milky Way”.

Some of the map’s new insights came close to home, such as a catalogue of more than 156,000 asteroids in our Solar System “whose orbits the instrument has calculated with incomparable precision,” Francois Mignard, a member of the Gaia team, told AFP.

But Gaia also sees beyond the Milky Way, spotting 2.9 million other galaxies as well as 1.9 million quasars — the stunningly bright hearts of galaxies powered by supermassive black holes.

The Gaia spacecraft is nestled in a strategically positioned orbit 1.5 million kilometres (937,000 miles) from Earth, where it has been watching the skies since it was launched by the ESA in 2013.

The observation of starquakes, massive vibrations that change the shape of the distant stars, was “one of the most surprising discoveries coming out of the new data”, the ESA said.

Gaia was not built to observe starquakes but still detected the strange phenomenon on thousands of stars, including some that should not have any — at least according to our current understanding of the universe.

– ‘Turbulent’ galaxy –

“We have a fantastic new gold mine to do the asteroseismology of hundreds of thousands of stars in our Milky War galaxy,” said Gaia team member Conny Aerts.

Gaia has surveyed more than 1.8 billion stars but that only represents around one percent of the stars in the Milky Way, which is about 100,000 light years across.

The probe is equipped with two telescopes as well as a billion-pixel camera, which captures images sharp enough to gauge the diameter of a single strand of human hair 1,000 kilometres (620 miles) away.

It also has a range of other instruments that allow it to not just map the stars, but measure their movements, chemical compositions and ages.

The incredibly precise data “allows us to look more than 10 billion years into the past history of our own Milky Way,” said Anthony Brown, the chair of the Data Processing and Analysis Consortium which sifted through the massive amount of data.

The results from Gaia are already “far beyond what we expected” at this point, Mignard said.

They show that our galaxy is not moving smoothly through the universe as had been thought but is instead “turbulent” and “restless”, he said.

“It has had a lot of accidents in its life and still has them” as it interacts with other galaxies, he added. “Perhaps it will never be in a stationary state.”

“Our galaxy is indeed a living entity, where objects are born, where they die,” Aerts said.

– ‘Tens of thousands of exoplanets’ –

“The surrounding galaxies are continuously interacting with our galaxy and sometimes also falling inside it”.

Around 50 scientific papers were published alongside the new data, with many more expected in the coming years.

Gaia’s observations have fuelled thousands of studies since its first dataset was released in 2016.

The second dataset in 2018 allowed astronomers to show that the Milky Way merged with another galaxy in a violent collision around 10 billion years ago.

It took the team five years to deliver the latest data, which was observed from 2014 to 2017.

The final dataset will be released in 2030, after Gaia finishes its mission surveying the skies in 2025.

Monday’s release confirmed only two new exoplanets — and 200 other potential candidates — but far more are expected in the future.

“In principle Gaia, especially when it goes on for the full 10 years, should be capable of detecting tens of thousands of exoplanets down to Jupiter’s mass,” Brown said.