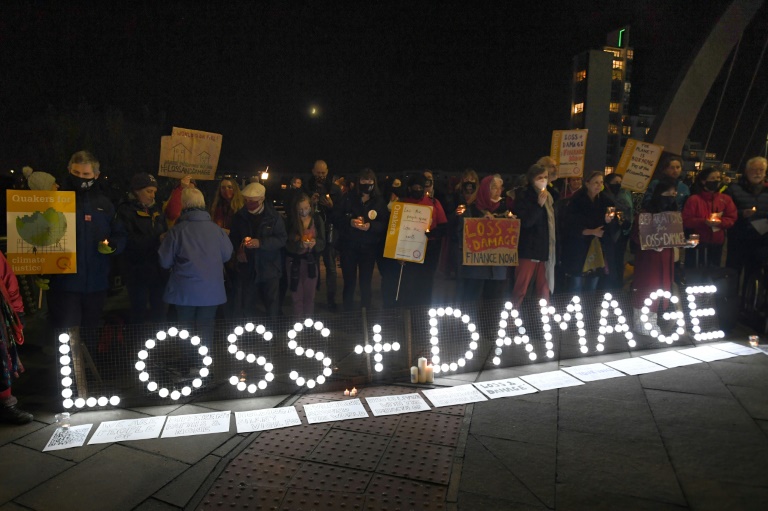

Climate activists holding a vigil for people around the world experiencing the most severe climate impacts during the UN COP26 conference in Glasgow

Vulnerable nations least responsible for planet-heating emissions have been battling for three decades for wealthy polluters to cough up the cash for climate damages.

Their final push took barely two weeks.

The “loss and damage” inflicted by climate-induced disasters was not even officially up for discussion when UN talks in Egypt began.

But a concerted effort among developing countries to make it the defining issue of the conference melted the resistance of wealthy polluters long fearful of open-ended liability, and gathered unstoppable momentum as the talks progressed.

In the end a decision to create a loss and damage fund was the first item confirmed on Sunday morning after fraught negotiations went overnight with nations clashing over a range of issues around curbing planet-heating emissions.

“At the beginning of these talks loss and damage was not even on the agenda and now we are making history,” said Mohamed Adow, executive director of Power Shift Africa.

“It just shows that this UN process can achieve results, and that the world can recognise the plight of the vulnerable must not be treated as a political football.”

Loss and damage covers a broad sweep of climate impacts, from bridges and homes washed away in flash flooding, to the threatened disappearance of cultures and whole island nations to the creeping rise of sea levels.

Observers say that the failure of rich polluters both to curb emissions and to meet their promise of funding to help countries boost climate resilience means that losses and damages are inevitably growing as the planet warms.

Event attribution science now makes it possible to measure how much global warming increases the likelihood or intensity of an individual cyclone, heat wave, drought or heavy rain event.

This year, an onslaught of climate-induced disasters — from catastrophic floods in Pakistan to severe drought threatening famine in Somalia — battered countries already struggling with the economic effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and soaring food and energy costs.

“Everyone also now realises that things have gone way beyond our control,” said Harjeet Singh, head of global political strategy at Climate Action Network International.

– Who pays? –

The agreement was a high-wire balancing act, over seemingly unbridgeable differences.

On the one hand the G77 and China bloc of 134 developing countries called for the immediate creation of a fund at COP27, with operational details to be agreed later.

Richer nations like the United States and European Union accepted that countries in the crosshairs of climate-driven disasters need money, but favoured a “mosaic” of funding arrangements.

They also wanted money to be focused on the most climate-vulnerable countries and for there to be a broader set of donors.

That is code for countries including China and Saudi Arabia that have become wealthier since they were listed as developing nations in 1992.

After last minute tussles over wording, the final loss and damage document decided to create a fund, as part of a broad array of funding arrangements for developing countries “that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change”.

Other key points of contention were left ambiguous, or put into the remit of a new transitional committee that will be tasked with coming up with a plan for making the decisions a reality for the 2023 UN climate summit in Dubai.

A reference to expanding sources of funding, “is vague enough to pass”, said Ines Benomar, researcher at think tank E3G.

But she said debates about whether China — the world’s biggest emitter — among others should maintain its status as “developing” was likely to reemerge next year.

“The discussion is postponed, but now there is more attention to it,” she said.

For his part, China’s envoy Xie Zhenhua told reporters Saturday that the fund should be for all developing countries.

However, he added: “I hope that it could be provided to the fragile countries first.”

– ‘Empty bucket’ –

Singh said other innovative sources of finance — like levies on fossil fuel extraction or air passengers — could raise “hundreds of billions of dollars”.

Pledges for loss and damage so far are miniscule in comparison to the scale of the damages.

They include $50 million from Austria, $13 million from Denmark and $8 million from Scotland.

Some $200 million has also been pledged — mainly from Germany — to the “Global Shield” project, launched by G7 economies and climate vulnerable nations.

The World Bank has estimated the Pakistan floods alone caused $30 billion in damages and economic loss.

Depending on how deeply the world slashes carbon pollution, loss and damage from climate change could cost developing countries $290 to 580 billion a year by 2030, reaching $1 trillion to 1.8 trillion in 2050, according to 2018 research.

Adow said that a loss and damage fund was just the first step.

“What we have is an empty bucket,” he said.

“Now we need to fill it so that support can flow to the most impacted people who are suffering right now at the hands of the climate crisis.”