Black ticks on their foreheads marking the eye to be operated on, dozens of patients in green overalls wait in line, beneficiaries of a pioneering Indian model that is restoring sight to millions.

With a highly efficient assembly line model inspired by McDonald’s, the network of hospitals of the Aravind Eye Care System performs around 500,000 surgeries a year — many for free.

More than a quarter of the world’s population, some 2.2 billion people, suffer from vision impairment. Of which one billion cases could have been prevented or have been left unaddressed, according to the World Vision Report by the World Health Organization.

There are an estimated 10 million blind people in India, with a further 50 million suffering from some form of visual impairment. Cataracts — clouding of the eye lens — is the main cause.

“The bulk of this blindness is not necessary because a lot of it is due to cataract which can be easily set right through a simple surgery,” said Thulasiraj Ravilla, one of the founding members of Aravind.

The hospital was set up by doctor Govindappa Venkataswamy who was inspired by McDonald’s ex-CEO Roy Kroc and learned about the fast-food chain’s economies of scale during a visit to the Hamburger University in Chicago.

“If McDonald’s can do it for hamburgers, why can’t we do it for eye care?” he famously said.

Aravind started as an 11-bed facility in 1976 in Madurai, a city in the southern state of Tamil Nadu but has expanded to care centres and community clinics across India.

– Grit and gratitude –

The model has been so successful it has been the subject of numerous studies including by Harvard Business School.

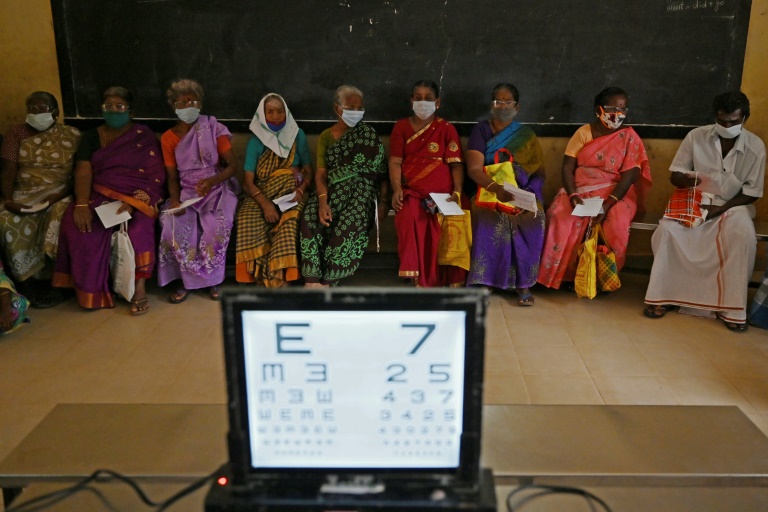

But it is the outreach camps which have been the cornerstone of its no-frills high-volume work — nearly 70 percent of India’s population lives in rural areas.

“It is the access that is the main concern, so we are taking the treatment to people rather than waiting for them to come for us,” Ravilla told AFP.

The free eye camps are a boon for those like Venkatachalam Rajangam who received care close to home.

Rajangam said he had to stop working because he was unable to see the money customers at his provisions store gave him, and also stumbled on the stairs or when out after dark.

The 64-year-old found out about a camp next to his village in Kadukarai, some 240 kilometres (150 miles) from Madurai, where doctors screened his eyes and detected a cataract in the left one.

Rajangam was taken in a bus with some 100 others to a shelter run by the hospital, which also provides basic meals and mats to sleep on free of charge, and underwent a procedure to remove the cataract.

“I thought the operation would be for an hour but within 15 minutes everything was over. But it didn’t feel rushed. The procedure was done properly,” Rajangam said after the bandage roll covering his eye was removed.

“I didn’t have to spend even a penny… God has created eyes, but they are the ones who restored my eyesight,” he gushed, clasping his hands in gratitude.

– ‘Practice on goat eyeballs’ –

Aravind eye surgeon Aruna Pai said the doctors receive rigorous training to make sure they can perform surgeries quickly.

The complication rate is less than two per 10,000 at Aravind compared to Britain or the United States where it ranges from 4-8 per 10,000, according to the hospital.

“We have wet labs where we are taught to operate on goats’ eyeballs. This helps us to sharpen our skills,” said Pai, who performs some 100 surgeries in a day.

Aravind said it does not take charity money but instead uses the revenue generated from paying customers to help cover the cost of those who need free treatment.

It reduces costs further by manufacturing lenses for cataract treatment at its own facility called Aurolab.

Aurolab currently produces more than 2.5 million of these lenses a year at a sixth of the cost of those previously imported from the US, the hospital said.

Rajib Dasgupta, a community health expert based in New Delhi, lauded the clinics: “The Aravind model has emerged as an important one in blindness prevention.”

But he warned that India still needed to look at root causes — including diet, hygiene, and sanitation — that could help avoid preventable blindness.

Dasgupta warned: “The communicable causes of blindness due to infectious conditions still exist and remain significant challenges.”

— This story is being published to coincide with World Sight Day —