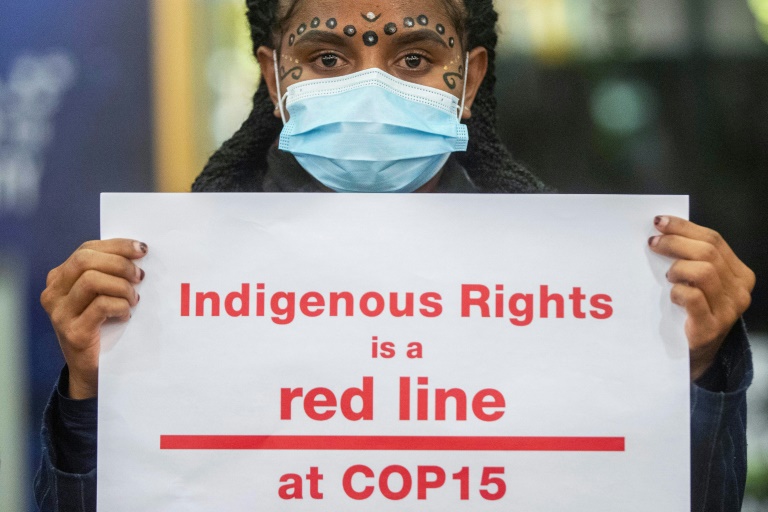

Global Youth Biodiversity Network holds a protest during the United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP15) in Montreal

Crucial UN talks aimed at sealing a “peace pact for nature” were entering their final stages Saturday, officially the last day the world’s environment ministers are gathered in Montreal for the COP15 meeting.

Whether they deliver a deal for biodiversity as ambitious as the Paris climate accord, endorse a watered-down text, or fail to agree on anything at all remains to be seen.

The negotiations officially run until December 19, but there are strong signs that ministers will be asked to stay on until the end, and the conference itself could run beyond the allotted time.

“We’re all going to be held accountable, by our future generation, our children and all life on Earth,” Chinese environment minister Huang Runqiu, the conference president, told fellow ministers.

China holds the presidency of COP15, but its strict Covid rules prevented it from hosting, leaving that task to Canada in deep winter.

At stake is nothing less than the future of the planet: whether humanity can roll back the habitat destruction, pollution and climate crisis that threaten an estimated one million plant and animal species with extinction.

The text is meant to be a roadmap for nations through 2030. The last 10-year plan, signed in Japan in 2010, failed to achieve any of its objectives, a failure blamed widely on its lack of monitoring mechanisms.

Major draft goals now include a cornerstone pledge to protect 30 percent of the world’s land and oceans by 2030, an ambitious objective being compared to the Paris deal commitment to hold long-term planetary warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius — or at least to 2.0 degrees.

– Money matters –

In all, there are more than 20 targets. They include reducing environmentally destructive farming subsidies, requiring businesses to assess and report on their biodiversity impacts, and tackling the scourge of invasive species.

Representatives of Indigenous communities — who safeguard 80 percent of the world’s remaining biodiversity — want their rights to practice stewardship of their lands to be enshrined in the final agreement.

The thorny issue of how much money the rich countries — collectively known as the Global North — will send to the Global South, home to most of the world’s biodiversity, has emerged as the biggest sticking point.

Developing countries say developed nations grew rich by exploiting their resources and the South should be paid to preserve its ecosystems.

Several countries have announced new commitments either at the COP or recently, with Europe emerging as a key leader. The European Union has committed seven billion euros ($7.4 billion) for the period until 2027, double its prior pledge.

But these commitments are still well short of what observers say is needed, and what developing countries are seeking.

Brazil has led that charge, proposing flows of $100 billion annually, compared to the roughly $10 billion at present.

But France has hit back, saying developed countries will only step up funding if developing countries agree to more ambitious plans, including on reducing heavy pesticide use by agricutural industries.

“We cannot have, on the one hand, some tears for species but no real commitments at the end of this COP,” French environment minister Christophe Bechu said Friday.

Whether international aid is delivered via a new fund, an existing mechanism called the Global Environment Facility (GEF), or a halfway solution involving a new “trust fund” within the GEF is still up for debate.

With the clock ticking, over 3,000 scientists have written an open letter to policymakers, calling for immediate action to stop the destruction of critical ecosystems.

“We owe this to ourselves and to future generations — we can’t wait any longer,” they said.

Beyond the moral implications, there is the question of self-interest: $44 trillion of economic value generation — more than half the world’s total GDP — depends on nature and its services.