EU vows more emissions cuts at UN climate talks

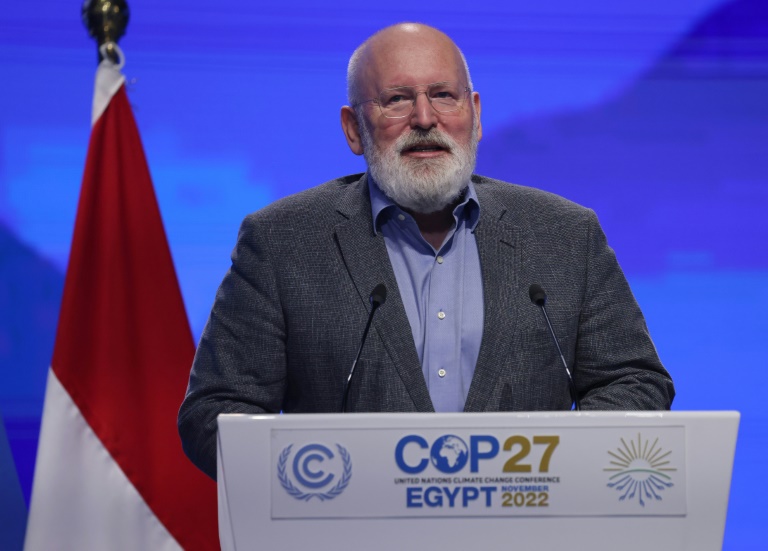

European Commission Vice President Frans Timmermans vows the EU will step up its emissions cuts at UN climate talks in Egypt, dismissing suggestions the bloc is backtracking in the face of the Ukraine conflict

The EU vowed to step up its emissions cuts at UN climate talks on Tuesday as developing nations admonished rich polluters for falling short on efforts to help them cope with global warming.

The COP27 conference in Egypt has been dominated by calls for wealthy nations to fulfil pledges to fund the green transitions of poorer countries least responsible for global emissions, build their resilience and compensate them for climate-linked losses.

The meeting comes as global emissions are slated to reach an all-time high this year, making the aspirational goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to preindustrial levels ever more elusive.

European Commission Vice President Frans Timmermans told delegates that the European Union will update its climate commitment as it will be able to exceed its original plan to cut emissions by 55 percent by 2030.

The 27-nation bloc will now be able to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 57 percent from 1990 levels, he said.

“The European Union is here to move forwards, not backwards,” Timmermans told COP27 delegates.

The invasion of Ukraine by fossil fuel exporter Russia has cast a shadow over the talks in Egypt, with activists accusing Europeans of seeking to tap Africa for natural gas following Russian supply cuts.

But Timmermans denied that the 27-nation bloc was in a “dash for gas” in the wake of the Ukraine conflict.

“So don’t let anybody tell you here or outside that the EU is backtracking,” he said.

Campaigners said the EU announcement did not go far enough.

“This small increase announced today at COP27 doesn’t do justice to the calls from the most vulnerable countries at the front lines,” said Chiara Martinelli, of Climate Action Network Europe.

“If the EU, with a heavy history of emitting greenhouse gases, doesn’t lead on mitigating climate change, who will?”

– North vs South –

COP27 has exposed deep divisions between wealthy polluters and nations vulnerable to the most ferocious climate impacts.

“The lack of leadership and ambition on mitigating greenhouse gas emissions is worrisome,” said Senegalese Environment Minister Alioune Nodoye, speaking on behalf of the Least Developed Countries Group.

Belize Climate Change Minister Orlando Habet called for more action from the G20 group of the world’s wealthiest nations, which are responsible for 80 percent of global emissions and are meeting at summit in Indonesia.

“In how many COPs have we been arguing for urgent climate action? And how many more do we need, how many lives do we need to sacrifice,” Habet said.

UN climate talks often go into overtime and this year’s meeting, due to end on Friday, could be no different.

The first draft of the final declaration only has bullet points so far, with a line on the “urgency of action to keep 1.5C in reach”.

Wealthy and developing nations are sharply divided over money at COP27.

Developing countries says this year’s floods in Pakistan, which have cost the country up to $40 billion, have highlighted the pressing need to create a “loss and damage” compensation fund.

In a small breakthrough, the United States and European Union agreed to have the issue discussed at COP27.

But Western governments favour using existing financial channels instead of building a new mechanism.

The draft declaration mentions the “need for funding arrangements to address” loss and damage — language used by the United States and Europeans since COP27 started on November 6.

“Loss and damage must remain firmly on the table as we continue to witness increasing appearances of severity of climate change impacts everywhere,” Samoan Prime Minister Fiame Naomi Mata’afa told delegates.

“The financial burden for loss and damage falls almost entirely on affected countries and not those most responsible for climate change.”