Sheltered by snow-spattered mountains, the Stordalen mire is a flat, marshy plateau, pockmarked with muddy puddles. A whiff of rotten eggs wafts through the fresh air.

Here in the Arctic in Sweden’s far north, about 10 kilometres (six miles) east of the tiny town of Abisko, global warming is happening three times faster than in the rest of the world.

On the peatland, covered in tufts of grass and shrubs dotted with blue and orange berries and little white flowers, looms a moonlander-like pod hinting at this far-flung site’s scientific significance.

Researchers are studying the frozen — now shapeshifting — earth below known as permafrost.

As Keith Larson walks between the experiments, the boardwalks purposefully set out in a grid across the peat sink into the puddles and ponds underneath and tiny bubbles appear.

The distinct odour it emits is from hydrogen sulfide, sometimes known as swamp gas. But what has scientists worried is another gas rising up with it: methane.

Carbon stores, long locked in the permafrost, are now seeping out.

Between carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane, permafrost contains some 1,700 billion tonnes of organic carbon, almost twice the amount of carbon already present in the atmosphere.

Methane lingers in the atmosphere for only 12 years compared to centuries for CO2 but is about 25 times more potent as a greenhouse gas over a 100-year period.

Thawing permafrost is a carbon “time bomb”, scientists have warned.

– Vicious circle –

In the 1970s, “when researchers first started showing up and investigating these habitats, these ponds didn’t exist”, says Larson, project coordinator for the Climate Impacts Research Centre at Umea University, based at the Abisko Scientific Research Station.

“The smell of the hydrogen sulfide, that’s associated with the methane that’s being released — they wouldn’t have smelled that to the extent we do today,” adds Larson, who measures how deep the so-called active layer is by shoving a metal rod into the ground.

Permafrost — defined as soil that stays frozen year-round for at least two consecutive years — lies under about a quarter of the land in the Northern Hemisphere.

In Abisko, the permafrost beneath the mire can be up to tens of metres thick, dating back thousands of years. In parts of Siberia, it can go down over a kilometre and be hundreds of thousands of years old.

With average temperatures rising around the Arctic, the permafrost has started to thaw.

As it does so, bacteria in the soil begin to decompose the biomass stored within. The process releases the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide and methane — further accelerating climate change in a vicious circle.

A few minutes’ drive away at the much smaller Storflaket mire, researcher Margareta Johansson has tracked the thawing permafrost since 2008 by measuring the active layer, the part of the soil that thaws in summer.

“In this active layer, where measurements started in 1978, we have seen it become between seven and 13 centimetres (2.8 and 5 inches) thicker every decade,” says Johansson, from Lund University’s department of physical geography and ecosystem science.

“This freezer that has kept plants frozen for thousands of years has stored the carbon that then can be released as the active layer gets thicker,” she adds.

– At a tipping point? –

By 2100, the permafrost could have significantly thawed if CO2 emissions are not reduced, experts on oceans and the cryosphere from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have warned.

The Arctic’s average annual temperature rose by 3.1 degrees Celsius (37.6 degrees Fahrenheit) from 1971 to 2019, compared to 1C for the planet as a whole, the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme said in May.

So could the permafrost reach a tipping point? That is, a temperature threshold beyond which an ecosystem can tip into a new state and risk disturbing the global system.

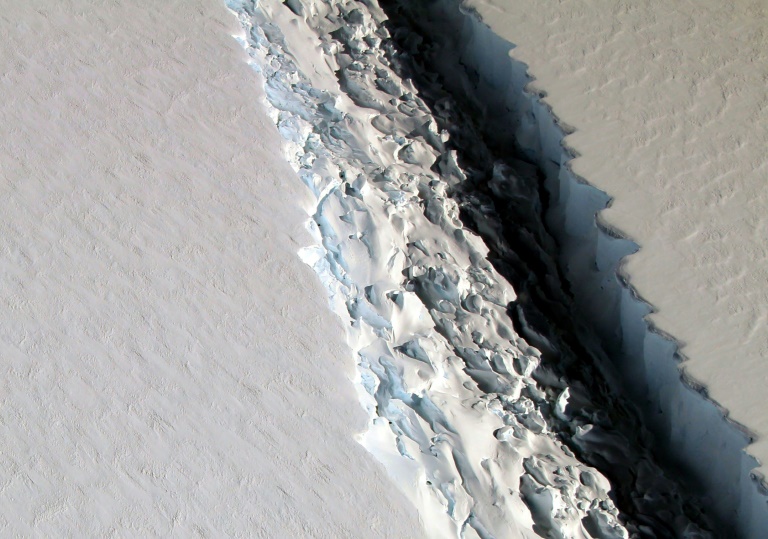

It’s feared, for example, that the Amazon tropical forest could turn into a savannah or that the ice sheets atop Greenland and West Antarctica could melt entirely.

“If all the frozen carbon would be released, it would almost triple the concentration of carbon in the atmosphere,” Gustaf Hugelius, from Stockholm University who specialises in the carbon cycles of permafrost, tells AFP.

“But that will never happen,” he quickly adds. The thawing of the permafrost, he says, will not take place all at once, nor will all the carbon be released in a giant puff.

Rather, it will seep out over decades, even hundreds of years.

The big issue with permafrost is that the thawing and accompanying carbon release will continue even if human emissions are cut.

“We have just begun activating a system that will react for a very long time,” Hugelius says.

– Cracks in the ground –

In Abisko, a small lakeside town with traditional red brick and wooden buildings known as a popular spot for viewing the northern lights, telltale signs of thawing permafrost are there if you know where to look.

Tears in the ground have opened up and slumping soil is visible around the picturesque town. Rows of telephone poles are tilting because the ground has started to shift.

In Alaska, where permafrost is found beneath nearly 85 percent of the land, thawing permafrost is causing roads to warp.

Cities in Siberia have seen buildings start to crack as the ground shifts. In Yakutsk, the world’s largest city built on permafrost, some buildings have already had to be demolished.

The deterioration of permafrost affects water, sewage and oil pipes as well as buried chemical, biological and radioactive substances, Russia’s environment ministry said in a report in 2019.

Last year, a fuel tank ruptured after its supports suddenly sank into the ground near the Siberian city of Norilsk, spilling 21,000 tonnes of diesel into nearby rivers.

Norilsk Nickel blamed thawing permafrost that had weakened the plant’s foundation.

Across the Arctic, permafrost thaw could affect up to around two thirds of infrastructure by mid-century, according to a draft IPCC report, seen by AFP in June ahead of its scheduled release by the UN in February.

More than 1,200 settlements, 36,000 buildings and four million people would be affected, it said.

It can lead to other dramatic changes in the landscape too, such as trapping water to form new ponds or lakes, or opening up a new path for water drainage, leaving the area completely dry.

– Threatening Paris goals –

The planet-warming gases escaping from permafrost threaten the hard-won Paris climate goals, scientists have warned.

Countries that signed the 2015 treaty vowed to cap the rise in global temperatures at well below 2C — 1.5C if possible — compared to preindustrial levels.

To have a two-thirds chance of staying under the 1.5C cap, humanity cannot emit more than 400 billion tonnes of CO2, the IPCC recently concluded.

At current rates of emissions, our “carbon budget” would be exhausted within a decade.

But carbon budgets do “not fully account for” the wild card of a rapid discharge in greenhouse gases from natural sources in the Arctic, warned a study this year, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

Many climate models currently don’t take permafrost into account because it is difficult to project the net effects of the permafrost thawing, Hugelius says.

Emissions in some areas are offset by the “greening of the Arctic” as certain plants thrive in the warmer temperatures, he adds.

However, the latest IPCC report from August did raise the issue of melting permafrost and stated that “further warming will amplify permafrost thawing”, he says.

Action taken now can still have a strong effect on the speed of the thaw, Larson stresses.

Even if “we actually don’t have control over the rate of thaw of the permafrost soils” that doesn’t mean “we shouldn’t turn off the fossil fuels and change how we live on this planet”, he says.

Some changes driven by warming temperatures in the Arctic are already irreversible, he adds sadly.

– Tradition slipping away –

“Around here we’ve been reindeer herding for at least 1,000 years,” says Tomas Kuhmunen, a member of the indigenous Sami community.

Wearing a peaked bobble hat in traditional blue, red and yellow, he is standing on top of Luossavaara mountain overlooking Kiruna, Sweden’s northernmost town that has grown up around an iron mine.

Kuhmunen, 34, works with the Sami Parliament but is also a reindeer herder, a practice passed down the generations for as far back as he can trace his family records, which is until the 1600s.

Unlike in his ancestors’ days, modern times have forced the grazing reindeer to negotiate roads, rail tracks, wind power plants and mines.

Today, they must also adapt to the warming climate.

Traditionally, the reindeer roam freely part of the year, with the cold weather in autumn quickly freezing the ground, which stayed frozen through the winter snowfalls.

“That creates a good ground for the reindeer to dig up the lichen,” Kuhmunen says, explaining that they can smell lichen through as much as a metre of snow.

But changing weather patterns have affected the availability of food.

Unseasonably high temperatures cause the snow to thaw and freeze again when the cold returns, building up thicker layers of ice that prevent the reindeer from digging down through the snow.

The animals struggle to find enough to eat, forcing Kuhmunen to spread the herd out over a much larger area to find food.

That means he has to go tens of kilometres more to keep an eye on them, using a snowmobile rather than skis.

“In many instances down in the forest we are grazing what were our forefathers’ ‘Plan C’ type of pastures,” the bearded herder says.

According to Sweden’s Sami Parliament, about 2,500 people depend on reindeer for their livelihood.

The changes facing herders are of concern to the UN’s IPCC climate science advisory panel.

In Siberia “nomadic reindeer herding and cryosphere fishing livelihoods are vulnerable to permafrost thaw, which alters northern landscapes and lakes as well as rain-on-snow events… ” its draft report said.

“These people are endemically adapting via key decisions to alter nomadic routes, pasture uses and seasonal land use.”

When necessary, Kuhmunen puts out pellets in troughs for the reindeer to feed on.

“It’s a way to have the reindeer survive, but it’s not desirable” and it’s not “economically sustainable”, he insists.

It reflects a trend in Sweden, Norway and Finland, according to researchers from northern Sweden’s Umea University.

But herders do not consider it “a long-term solution”: feeding the reindeer directly is harmful for their health and behaviour — reindeer become “too tame”, threatening the traditional lifestyle, they noted last year.

– Shrinking –

On the south peak of the dramatic Kebnekaise massif, 70 km away, year after year Ninis Rosqvist is seeing the impact of a warming climate before her very eyes.

Nimble as a mountain goat, the 61-year-old glacial researcher expertly climbs up under a cloudless blue sky to place an antenna in the freshly-fallen snow to measure the altitude.

Before she gets her answer, she knows the glacier — 150 km north of the Arctic Circle — is smaller than the last time she was there.

The mountaintop glacier has shrunk by more than 20 metres (66 feet) since the 1970s.

The GPS shows she is 2,094.8 metres up.

Until two years ago, it was Sweden’s highest peak.

“In the past 30 years, it’s been melting more than previously, and in the last 10 years it’s been even more,” Rosqvist, a Stockholm University geography professor, says, adding that summers especially have been unusually warm with recurring heatwaves.

“We can see the effect of it because it’s like: ‘Wow (the glaciers) they’re thin, they have melted so much’.”

Most glaciers in Sweden are likely doomed, Rosqvist believes. Here, the loss won’t have much of an impact since there is already enough freshwater from rain and snowmelt.

But it’s a strong signal to the world.

In South America and around the Himalayas, people depend on the yearly meltwater from glaciers for drinking water and irrigation.

And in Greenland, the ice sheets hold enough water to raise global sea levels by up to seven metres.

For many researchers, an important lesson from the Arctic is that some of these systems are outside human control.

But, says Larson, changing how we live on the planet by cutting manmade emissions “will be the beginning of that process of adapting to a climate that will be warming for a very long time”.