US duo win Nobel for work on temperature and touch

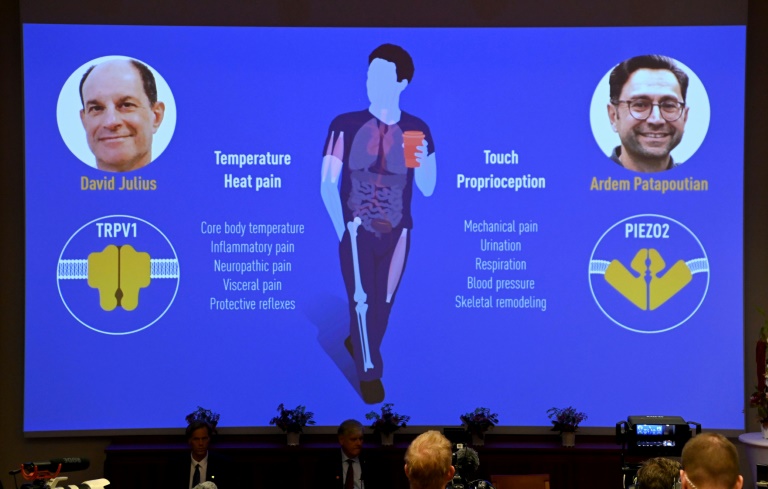

US scientists David Julius and Ardem Patapoutian on Monday won the Nobel Medicine Prize for discoveries on receptors for temperature and touch.

“The groundbreaking discoveries… by this year’s Nobel Prize laureates have allowed us to understand how heat, cold and mechanical force can initiate the nerve impulses that allow us to perceive and adapt to the world,” the Nobel jury said.

The pair’s research is being used to develop treatments for a wide range of diseases and conditions, including chronic pain.

Julius, who in 2019 won the $3-million Breakthrough Prize in life sciences, said he was stunned to receive the call from the Nobel committee early Monday.

“One never really expects that to happen …I thought it was a prank,” he told Swedish Radio.

The Nobel Foundation meanwhile posted a picture of Patapoutian next to his son Luca after hearing the happy news.

Our ability to sense heat, cold and touch is essential for survival, the Nobel Committee explained, and underpins our interaction with the world around us.

“In our daily lives we take these sensations for granted, but how are nerve impulses initiated so that temperature and pressure can be perceived? This question has been solved by this year’s Nobel Prize laureates.”

Prior to their discoveries, “our understanding of how the nervous system senses and interprets our environment still contained a fundamental unsolved question: how are temperature and mechanical stimuli converted into electrical impulses in the nervous system.”

– Grocery store research –

Julius, 65, was recognised for his research using capsaicin — a compound from chili peppers that induces a burning sensation –- to identify which nerve sensors in the skin respond to heat.

He told Scientific American in 2019 that he got the idea to study chili peppers after a visit to the grocery store.

“I was looking at these shelves and shelves of basically chili peppers and extracts (hot sauce) and thinking, ‘This is such an important and such a fun problem to look at. I’ve really got to get serious about this’,” he said.

Patapoutian’s pioneering discovery was identifying the class of nerve sensors that respond to touch.

Julius, a professor at the University of California in San Francisco and the 12-year-younger Patapoutian, a professor at Scripps Research in California, will share the Nobel Prize cheque for 10 million Swedish kronor ($1.1 million, one million euros).

The pair were not among the frontrunners mentioned in the speculation ahead of the announcement.

Pioneers of messenger RNA (mRNA) technology, which paved the way for mRNA Covid vaccines, and immune system researchers had been widely tipped as favourites.

While the 2020 award was handed out in the midst of the pandemic, this is the first time the entire selection process has taken place under the shadow of Covid-19.

Last year, the award went to three virologists for the discovery of the Hepatitis C virus.

– Media, Belarus opposition for Peace Prize? –

The Nobel season continues on Tuesday with the award for physics and Wednesday with chemistry, followed by the much-anticipated prizes for literature on Thursday and peace on Friday before the economics prize winds things up on Monday, October 11.

For the Peace Prize on Friday, media watchdogs such as Reporters Without Borders and the Committee to Protect Journalists have been mentioned as possible winners, as has the Belarusian opposition spearheaded by Svetlana Tikhanovskaya. Also mentioned are climate campaigners such as Sweden’s Greta Thunberg and her Fridays for Future movement.

Meanwhile, for the Literature Prize on Thursday, Stockholm’s literary circles have been buzzing with the names of dozens of usual suspects.

The Swedish Academy has only chosen laureates from Europe and North America since 2012 when China’s Mo Yan won, raising speculation that it could choose to rectify that imbalance this year. A total of 95 of 117 literature laureates have come from Europe and North America.

While the names of the Nobel laureates are kept secret until the last minute, the Nobel Foundation has already announced that the glittering prize ceremony and banquet held in Stockholm in December for the science and literature laureates will not happen this year due to the pandemic.

Like last year, laureates will receive their awards in their home countries.

A decision has yet to be made about the lavish Peace Prize ceremony held in Oslo on the same day.