Fears of worsening India floods as torrential rains wreak havoc

More than three million people have been affected by the annual monsoon deluge as torrential rains pummel eastern India, officials said Wednesday, with villagers fleeing to higher ground and wildlife sanctuaries underwater.

Monsoons are crucial to replenishing water supplies after the scorching summer season but also cause widespread death and destruction across South Asia each year.

The storms have been worsened by climate change, experts say.

India’s poorest state Bihar and wildlife-rich Assam have been hit by incessant rains for a week, with swollen rivers bursting their banks and stranding thousands of people in villages.

In Assam, water levels for the Brahmaputra — a mighty transborder Himalayan river system — have risen above their “danger levels”, a water resource department official told AFP.

Villager Amshar Ali said locals were struggling with basic needs.

“We are in great suffering. It is difficult to get food, drinking water and other essential items,” Ali told AFP.

“Many villagers do not have their own boats, so people are suffering.”

Farmer Liyakat Ali said he had to move his livestock to a friend’s property after his house was submerged.

“The floodwaters have risen to above four to five feet (1.2-1.5 metres) in the last two days,” he told AFP.

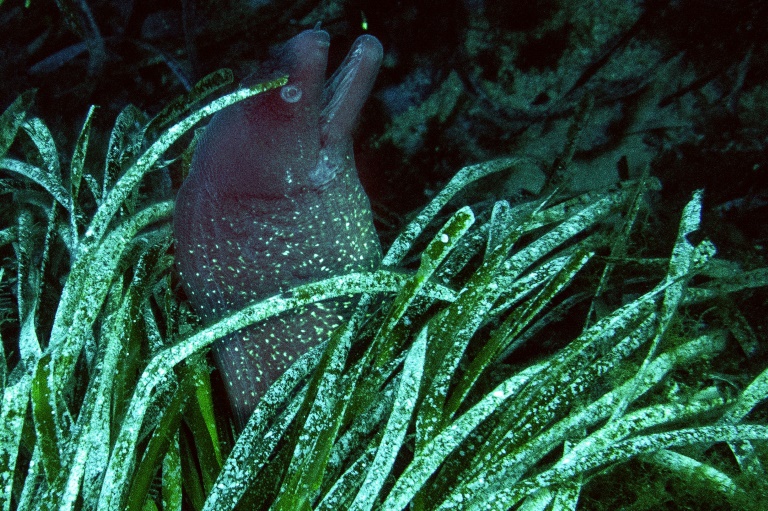

Up to 80 percent of the Kaziranga National Park and Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary — both along the Brahmaputra and home to rare one-horned rhinoceroses — were underwater, officials said.

“All the wild animals are taking shelter on higher lands in the sanctuary,” Pobitora ranger Nayanjyoti Das told AFP.

Assam officials said at least 11 animals — including two swamp deer, eight hog deer and one capped langur — have been killed in the floods.

“We have been surviving on dry food grains as our kitchen is in chest-deep water,” villager Prem Yadav told AFP from his rooftop, where he and his family have been sleeping since Saturday in Bihar’s Gopalganj district.

The homes of villagers in other low-lying areas were also inundated with floodwaters, forcing them to take shelter at nearby embankments and roads.

More than 3.2 million people in over 2,200 villages in 17 districts in Bihar have been impacted by the rising waters since last week, authorities said.

Some 215,000 people were evacuated from their homes.

Since the start of the monsoon season in June, some 43 people have died in Bihar, according to official data.

The India Meteorological Department said the heavy downpours could continue in the two states until Thursday.

strs-grk/axn